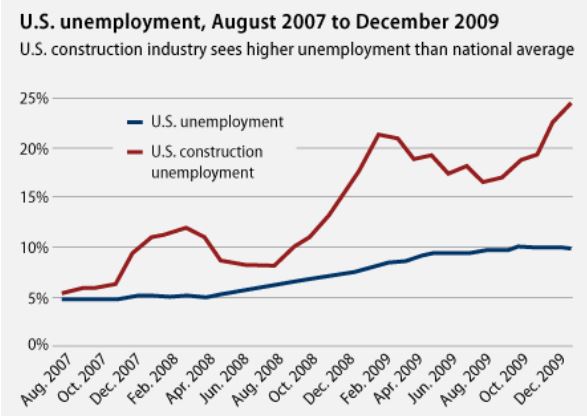

For those involved in construction 2008-2012, we had a taste of what the 1930’s may have been like. This was the era we sometimes still refer to as the “Tool Belt Recession”.

Many projects that were pending when the bottom dropped out were never started. Projects that were underway cut as many details as they could from their budgets. Contractors were laid off and very little new construction was underway. I suspect that during the 1930’s, like late 2008, more effort put into maintenance than new construction.

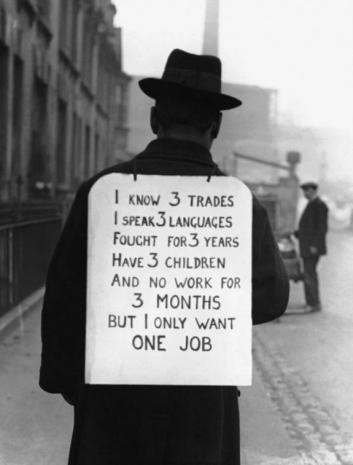

Depression Era Unemployment Off the Charts

By the time FDR took office in 1933, unemployment was off the charts. It was a staggering 25% for the country, and much higher in industrial cities. It seems only New Deal projects were the only ones going on. Projects like Lincoln Tunnel, Great Smoky Mountain National Park, Hoover Dam. And, the Highway connecting Miami to the Keys and the Grand Coulee Dam, to name a few.

Alpine Thrives During Great Recession

Thankfully, Alpine was fortunate during the Great Recession. Projects that had already been started generally followed through to completion. Our product is generally installed towards the tail-end of new construction, so we had residual orders that had been initiated, in some cases, 2 years prior. Where we saw challenges was more between 2011-2015 when new construction was coming around, but our part wasn’t needed yet. I mention this because our retrofit business kept us afloat through that period. Based on the few patents filed in the 1930’s, history seems to have repeated itself.

Depression Era Snow Guard Patents

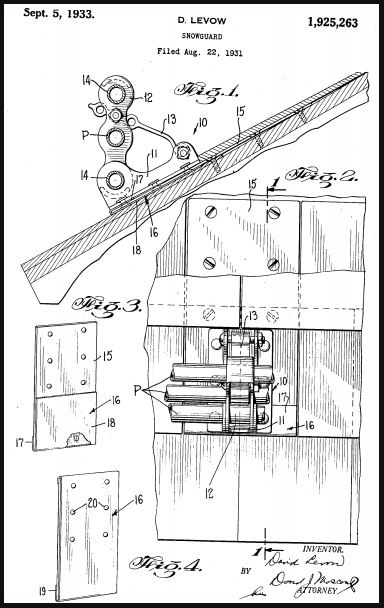

In August of 1931, David Levow of New York filed for patent #1925263 (below). Interestingly enough, the patent claims were focused more on a cushioning concern that would reduce or eliminate cracking of slate shingles due to the pressure asserted on them when the snow guard bracket was loaded with snow.

This is a good time to assert my theory about snow guards for steep-slope roofing applications. As snow and ice accumulate on a hard roofing surface like slate, clay tile, metal, glass and most synthetic shingle surfaces, a mass will often accumulate. This tends to happen more at night than during the day when the sun has warmed the roof surface and snow tends to melt a little as it lands on a warm surface. Certainly, weather conditions can vary, and it’s safe to say that conditions for accumulation are more likely to occur at night on a cold roof than during the day on a warm roof.

As temperatures rise (to be discussed in a separate blog along with ice damming), gravity pulls the running water down to the roof surface. On hard roof surfaces, the water creates a layer between the roof surface and the snow mass, creating a frictionless surface that might even be described as a lubricant. When this happens, the snow and ice mass release.

The Importance of Testing Snow Guards

The importance of pointing this out is to illustrate that the release happens at the roof surface, not at some ambiguous point elevated off the roof surface. ((It’s different with mountain avalanches – typically the result of ice layers that created layers of release faults). What this means is that a snow guard needs to be tested and functional in a shear mode.

When snow guards are tested in shear, they tend to compress the roof below the pad or pipes. Failure occurs when either the pad or pipe bracket deforms and is no longer functional, the base plate or strap attaching the device to the roof lifts upward, causing the pad to bend or twist, the fasteners holding the device in place fail, or the snow guard device causes damage to the roof shingles (cracks, holes, splits, etc.) This is an extremely important topic within snow guard design.

Alpine SnowGuards’ PP115 Pipe-Style Snow Guard

Alpine makes a snow guard system called the PP115 (shown below, installed on the roof at Camden Yards in Baltimore, MD). If the proper quantity of these parts are attached to a capable structural member, the user can park a tank against them and they won’t come off. However, that “tank” mass has long since either wrecked the roof or collapsed the building. The point is that snow guard design isn’t just about physical design. It’s about pressing pads out sufficiently to achieve the desired goal while not causing damage to roof shingles.

Back to David Levow’s Design . . .

In 1931, I imagine that snow guards were damaging slate and other shingle-style roofs as they or the roofing shingles failed. Based on my experience, I’m pretty certain that the pipe brackets of the era were being installed too far apart, and typically in one tier, at the outside edge of the load bearing wall of the structure. Depending on the project variables (snow load, pitch, square footage), the brackets would compress into the shingles. Levow reasons that a cushion could help, applies for a patent, and it issues in 1933.

Our Experience with Historical Work

As a side note to this cushion idea, given all of the historical work I did during the 1980’s-1990’s, I never removed anything that had a cushion device. However, I did move a lot of Levow’s pipe guards (shown in this patent detail), and in many cases reinstalled them with new roofing materials. That said, the Levow design is a great design, it just probably never needed a cushion. More likely, it needed closer bracket spacing, and in many cases, more tiers of snow guards to accommodate the compressive capability of the roofing materials they were being used on.

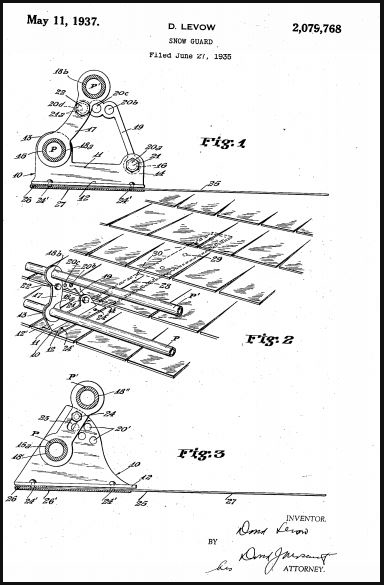

One additional note about Levow: He was awarded patent #2079768 in 1937 (below).

This was a two-pipe bracket designed to retrofit an existing slate roof without removing shingles. Ironically this bracket had a 2” base strap made of galvanized sheet metal.

“The roofing public wanted a pipe-style retrofit . . .”

So, what happened? This design had no cushion, a narrow base that would compress into the slate, and attached with 2 nails (yes, I’ve taken these snow guards off, too, but discarded them as quickly as I could get them removed so I could repair the mess). My read on it… the market said something like, “David, we like the snow guard design, but the cushion doesn’t make a bit of difference. David’s response probably went like this: “Fine, you like my design, what else do you need?” The roofing public wanted a pipe-style retrofit. It never really worked properly, but it sure as heck was easy to install.

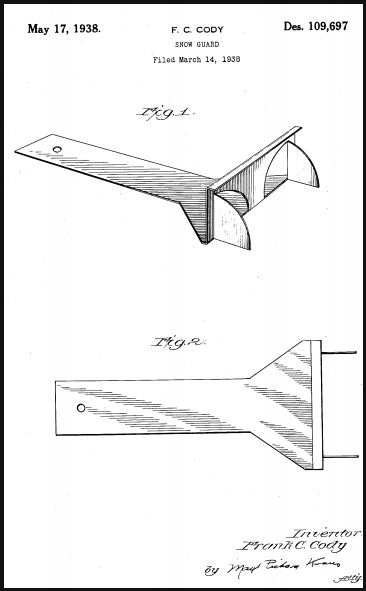

In 1938, Frank Cody of the Chicago area had a design patent for a sheet metal application – #D109697.

1940s Sees Halt in Snow Guard Design

It was another Emri Clark knock-off, but to Cody’s credit, it at least looked a little different. I think some of the sheet metal designs, this being one of them, originated as a means of keeping guys busy during periods of inclement weather. After all, if you needed to buy them anyway, why not use depression-era labor / wages to do something constructive. Today that $30.00-40.00/ hr. guy could create shop-fabricated snow guards – although the good deed of keeping him busy would likely be punished by the reality of being priced out of the market.

As we entered the 1940’s, snow guard design pretty much came to a screeching halt, as did most industries of the era, thanks to WWII. Come back next time and learn more about the snow guard designs of 1941-1950!

Until then,

Brian Stearns

President & Founder, Alpine SnowGuards

We keep snow in its place

888.766.4273

Sign up to start using our Online Project Calculator for an immediate layout and project pricing!

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter and keep up on the latest industry and Alpine news, products, and upcoming events!

Alpine SnowGuards designs, engineers, and manufactures snow management systems from our facilities in Morrisville, VT. We work closely with leading roofing contractors, engineering firms, developers, and roofing manufacturers to ensure we deliver quality products that do what we say they’ll do. Alpine SnowGuards can help a building qualify for LEED® credits.

(Images from: USPTO, photodoto.com, Home Performance Resource Center)